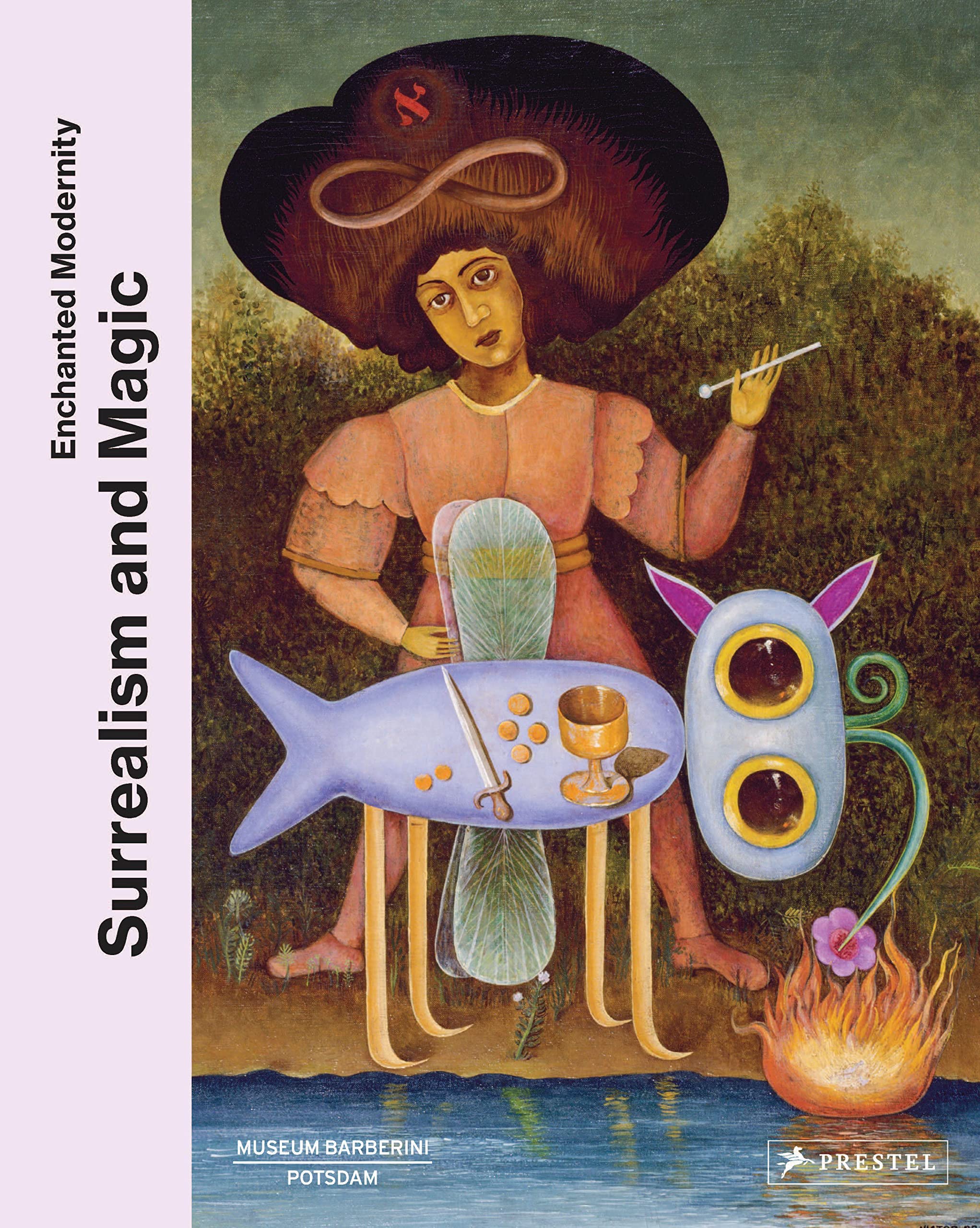

The Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity exhibition included some sixty artworks from dozens of museums and collections and was hosted by the Peggy Guggenheim (9 April – 26 September 2022) and Museum Barberini, Potsdam (22 October 2022 – 29 January 2023). The associated catalog consists of eleven essays by eight authors: Gražina Subelyté, Daniel Zamini, and Victoria Ferentinou each contributed two papers. These three also contributed to Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvelous, edited by Tessel B. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou, and Daniel Zamani (Routledge 2018). Essays by Kristofer Noheden, Gavin Parkinson, and Susan Aberth are also found in both volumes. Surrealism, Occultism and Politics is a polished academic study that emphasizes surrealist writing and has very few illustrations. Surrealism and Magic is likewise a scholarly production, but its exhibition catalog format will appeal to a larger audience. It emphasizes the visual arts by way of over one hundred full-page color plates, numerous full-page details, and additional color illustrations in the text margins. The first plates are located after the sixth essay and the rest are placed in sets after each of the others. The essays and plates are preceded by a preface and acknowledgements and followed by a glossary by Helen Bremm, notes, list of works, selected bibliography, list of authors with short biographies, a colophon, and image credits. Video clips of the exhibition halls and commentaries of some of the included works are available at the exhibition website.*

The essays are arranged more or less chronologically, with overlap in the discussion of the movement's phases, themes, and artists. All reference one or more of several publications by André Breton as guideposts to the movement's development and ambiguous interpretation of "magic," including his "Manifesto of Surrealism" (1924), Nadja (1928), the Second Manifesto (1929), "Prolegomena to a Third Surrealist Manifesto or Else" (1942), Arcanum 17 (1945), and L'art magique (1957).** Other significant benchmarks are the International Surrealist Exhibition in London (1936), the International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris (1938), and the International Exhibition of Surrealism in Paris (1947), as well as the publication of Kurt Seligman's The Mirror of Magic: A History of Magic in the Western World (1948).***

The first essay is "Magical Beginnings: André Breton and the 'Occultation of Surrealism'" (17-31) in which Daniel Zamini makes special note of Breton's call for the "occultation of Surrealism" in his second manifesto and of the increasing interest he took in all things that might be embraced by the word occult from the early 1920s through the post-World War II period, primarily as a counter to excessive rationalism. Zamini finds that, from the beginning, the surrealists interpreted magic psychologically as a kind of metaphor for the omnipotence of thought. Max Ernst was one of the first of the visual artists to explore occult ideas, as did Breton in his Nadja, which is described as indicative of "the movement's vociferous embrace of magic, showing modern life in the metropolis of Paris as entirely suffused with a marvelous dimension [...] (31)." Here, Zamini elides the meanings of magic and the surrealist "marvelous" and thereby hints at an explanation for the book's title; both of which, unfortunately, might easily conjure surreality as a brand of modern day spiritual fairydust.

In the second essay, "Modern Minotaurs: Surrealism, Myth, and Magic in the 1930s" (33- 45), Kristoffer Noheden considers the surrealists' developing interest in myth during the 1930s as a corollary to their interest in magic with both understood as forms of nonrational discourse that engaged symbols to connect various levels of reality and also moved beyond the individual to the universal. Giving special attention to the rise of Fascism in Germany and Italy at the time, Noheden addresses work by Giorgio de Chirico, Ernst, and Masson.

In the third essay, "Metaphors of Change: Surrealism, Magic, and World War II" (47- 57), Gražina Subelyté highlights the significance of the 1938 exhibition in Paris, which included over two hundred works from fourteen countries. Subelyté pays particular attention to the horrors of WWII as instrumental in inspiring the surrealists to embrace "magic and the occult primarily as metaphors of change, using them as symbolic discourses with which to map their faith in a time of healing after the war" (47)." It was in 1940-41 while waiting in Marseille to leave France that the Jeu de Marseille was created: this deck of cards represented surrealists and individuals that the surrealists admired in the manner of a re-envisioned Tarot. In addition to this collective project, Subelyté discusses Wolfgang Paalen's work, Frederick Kiesler's concept of "magic architecture" as a means of activating gallery spaces, Maya Deren's short film The Witch's Cradle, various surrealist journals, Breton's Arcanum 17 (1945), and the continuing interest in the occult, magic, and alchemy evident at the 1947 Exhibition.

In the fourth essay, "Of Kings and Queens: Alchemical Desire and the Surrealist Imagination" (59- 69), Alyce Mahon takes Breton's Arcanum 17 (1945) as the starting point for a discussion of the perceptions of women fostered by the surrealist perspective. Mahon emphasizes the works of Ernst, Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, and Dorothea Tanning, and the surrealists' interest in alchemy and countries they saw as still dominated by magic. In this latter regard, they were encouraged by Seligman's book on magic (1948). Mahon proposes that the engagement of women associated with surrealism, notably Carrington, Fini, and Tanning, with the gender-based models offered by alchemical symbolism and magical world views furthered Breton's long-established vision of the "occultation" of the movement.

In the fifth essay, "Modern Enchantress: Leonora Carrington, Surrealism, and Magic" (71- 81), Susan Aberth departs from the other essays insofar as she emphasizes the seriousness with which Carrington and other women artists took the actual practice of magic. They did not simply represent magical icons or make art with "primitive" characteristics, they actually used crystals, astrology, and herbs in rituals associated with art-making.

In the sixth essay, "Toward L'Art magique: Surrealism and Magic in the 1950s" (83-97), Gavin Parkinson sets the context for Breton's L'Art magique (1957) in the post-WWII period when the surrealists were expanding their knowledge of the occult, including magic, alchemy, and aspects of the paranormal to incorporate more practice-oriented and anthropological/ historical approaches. There is no indication in this essay, however, that the actual practice of "magic," such as that described in Aberth's essay was common among other surrealists. Parkinson notes that Breton realized the need for a more careful definition of magic and magic art than he had hitherto used and it was, in part, this need, that led to his 1957 book. Even here, however, Parkinson describes Breton as viewing magic as "an emancipatory force, linked to subjective wish-fulfillment and the creative power of the imagination (92)" and as finding magic to be essential to the earliest art and in subsequent eras as part of "the artist's persona as a magician, trickster, and illusionist" (97)." Readers may anticipate the forthcoming English translation of Breton's book (Fulgur 2024) as an opportunity to assess Breton's priorities for themselves.

The later essays highlight groups of artists and particular topics and each is followed by a set of plates, most of which illustrate the works discussed. As in the previous essays, each includes supplementary figures in the outside margins of the text. Zamini's second contribution "Hidden Dimensions: In Search of the Surreal" (101-105) is followed by reproductions of works by De Chirico, Yves Tanguy, Wolfgang Paalen, Matta, Óscar Domínguez, Max Ernst, Enrico Donati, and Kay Sage (Plates 1-27, pp. 107-35). Will Atkin's "Endless Metamorphosis: Surrealism and Alchemy" (137-41) is followed by reproductions of works by Victor Brauner, Ernst, André Masson, Wilhelm Freddie, Jacques Hérold, Jacqueline Lamba, Wilfredo Lam, Dalí, and Maria Martins (Plates 28-48, pp. 142-63). Victoria Ferentinou "Agents of Change: Women as Magical Beings" (165-69) is followed by reproductions of works by René Magritte, Paul Delvaux, Masson, Roland Penrose, Dorothea Tanning, and Leonor Fini (Plates 48-66, pp. 171-89). Subelyté's second contribution ""The Alchemy of Painting: Kurt Seligmann" (191-95) is followed by reproductions of works by Seligman (Plates 67-85, pp. 196-213). Ferentinou's second contribution "Sisters of the Moon: Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo" (215-19) is followed by reproductions of one work by Ernst and others by Carrington and Varo (Plates 86-101, pp. 220-37).

Surrealism and Magic is presented in a manner that fosters education about the movement, regardless of the reader's prior knowledge of the artists. The emphasis on the specific orientation points listed above is important to the book's success in this regard. Readers with more substantial backgrounds may find the alignment of the material under the rubric of "magic" somewhat labored, given that few of the surrealists, Breton included, seem to have been entirely clear on what magic is, being primarily interested in claiming it, whatever it might be, as part of their domain. With a few exceptions, their engagement with magic emphasized written and visual representations of their colonialist-infused and primitivist**** view of it and little or no real "practice" beyond games and creative strategies they invented their own rules for. Further, it seems that editorial strategy, rather than research, has dictated the placement of the word magic where other histories would use the broader occult, with magic, alchemy, the uncanny, the marvellous, and other practices and experiences as auxiliaries. Not surprisingly, however, the curators weren't overly interested in cultural critique: their goal was to affirm the value and continued relevance of historical surrealism.

For Tarot readers, that relevance is found in the essays addressing the women artists who actually undertook to practice magic in connection with their art, in the references to and illustrations of the Jeu de Marseille, in the essay on Seligman, and in the various notes to which some of the more interesting aspects of Tarot-related comment have been consigned. The Tarot-associated illustrations include reproductions from two historical decks, including Jean Dodal's Tarot de Marseille (The Juggler fig. 5 p. 141 and The Popess fig. 6 p. 141) and Arthur E. Waite and Pamela Colman Smith's Rider-Waite Tarot (1909) (The Star, fig. 11 p. 55; The Hermit fig. 2 p. 73; The Fool fig. 1 p. 192, and The Devil fig. 2, p. 192). Surrealist representations of Tarot-related images and images for the Jeu de Marseille include the following:

—Victor Brauner's "The Surrealist" (1947), detail p. 13, fig. 3 p. 140, Plate 30 p. 144; Hélène Smith, Siren of Knowledge—Lock fig. 6 p. 22 Plate 41 157; The Lovers: fig. 4 p. 140, Plate 31 p. 145

—André Breton: "Paracelsus, Magus of Knowledge—Lock" fig. 2 p. 49

—Oscar Dominguez: "Freud, Magus of Dreams—Star" fig. 7 p. 23 and Plate 42 p. 157

—Jacqueline Lamba: "Ace of Revolution—Wheel" Plate 38 p. 152; Baudelaire, Genius of Love—Flame Plate 39, p. 153

—André Masson: "Novalis, Magus of Love—Flame" fig. 1 p. 48

Tarot historians may also want to look up the earlier Surrealism, Occultism and Politics (Routledge 2018) at the library, if only for the black-and-white photograph of Brauner's "The Lovers" in situ at the 1947 Surrealist Exhibition as part of an altar (fig. 7.3 p. 139), as well as the brief anecdote about Breton's falling out with Seligman over a tarot card interpretation (167). Dedicated art historians may want to look up the 2018 publication because it offers more thorough treatments of the ambiguous definitions of occult, the marvellous, magic, and so forth, employed by the surrealists. Indeed, it seems possible that the very title Surrealism and Magic arose from a desire to distinguish it from the Routledge anthology, as well as Nadia Choucha's Surrealism and the Occult: Shamanism, Magic, Alchemy, and the Birth of an Artistic Movement (Destiny Books 1991), and a few other titles published over the past thirty years.

These observations aside, Magic and Surrealism: Enchanted Modernity is a catalog well worth adding to personal and library collections, not only for its copious illustrations, but as proof of the diversity of the surrealists' interests and of evolving perceptions of the movement and its goals.

*Peggy Guggenheim website: < https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/whats-on/exhibitions/surrealism-and-magic-enchanted-modernity/>.

**Fulgur Press plans to release the first English translation of L'Art magique in 2024.

*** Kurt Seligman's The Mirror of Magic: A History of Magic in the Western World (1948) is available for download at the Internet Archive.

****Evan Maurer's essay "Dada and Surrealism" in Volume II of "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984) and the extensive critique the entire exhibition inspired offer thorough treatments of this subject. None of these documents are cited in Modernism and Magic.

~review by Emily E. Auger

Exhibition and catalog by Gražina Subelyté and Daniel Zamani

Peggy Guggenheim Collection and the Museum Barberini in assoc. with Prestel, 2022