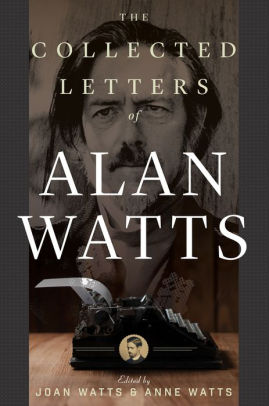

This monumental collection of letters begins with Watts at the tender age of 13 writing to his parents from boarding school in England and follows him through to the year of his death in 1973. Renowned for his work educating the Western world on the spiritual teachings of Asia, Alan Watts reached a kind of guru status which he rejected. He was an excellent scholar, devoted to his work, but also driven by human vices that ended his career as a priest and two of his marriages. Probably due to this unrealistic view of him as being more spiritually realized than the average person, his legacy has also been attacked for his all too human frailties. His daughters, Joan and Anne Watts, edited this collection with a gentle hand. At first the reader may think they are holding back, but good editing allows the story to develop without giving everything away all at once. Watts' daughters skillfully let his personal trials and foibles come to light without allowing them to obscure his life's work.

His early letters of 1928-37 are remarkable. We see Watts as an intellectually precocious young man who joins the Buddhist Lodge in London at age 15. He writes letters to Zen master Sokei-an Sasakim in Japan, and to C.G. Jung. Notably, Watts does not know that his grandmother will meet and marry the Zen master later or that he will socialize in circles of psychoanalysts throughout his career. His parents can't afford to send him to university, so he studies what he loves on his own. After marrying, Watts emigrates to America with his first wife, just as the rumblings of WWII begin.

It comes as a strange turn of events when the boy fascinated with Zen Buddhism decides that he should devote his life to the Episcopalian Church. He has the audacity to think that he has the knowledge to show people the proper way to see Christianity. He was at heart a Christian mystic who believed the lessons of Asian spirituality could breathe life into the ossified beliefs of the Christian faith. He loved ritual and symbols through which he felt communion with God but he was convinced that the faith was being presented to the faithful in a way that failed to inspire them. He talks of his unfavorable views towards the Gnostics, Manichaenism, American Protestants and Theosophists. Most readers will require a dictionary and prior studies in Christianity, Zen and Buddhism to follow his logic. Some liberal Christians may appreciate his learned and unorthodox ways of relating to the Gospel. Or better said, his views were not so much unorthodox as anachronistic drawing on older schools of Christian thought.

His strong opinions on topics that only a seminarian can love mean that the more religious discussion of his letters from 1938-1950 may turn off those whose primary interest in him are his Asian studies. I found this section the hardest to read knowing that this part of his life as a priest will fall away in divorce and infamy and “embarrassing gossip.” Yet, it is doubtful he would have attained his success as a philosopher, author, lecturer and teacher without the acumen and skills he learned as a priest. The seminary sharpened his writing and debating skills and ability to expound on abstract ideas. The daily work of a priest demanded discipline, a very full schedule, speaking in public to crowds, counseling one on one, and exposure to the problems of people in all stages of life. This work ethic and emotional intelligence transferred from the Episcopalian tradition straight over to his duties at the American Academy of Asian studies.

I really appreciated the historical details and descriptions of Watts' family life during WWII. His very British ways of describing some of the characters he meets is also amusing. Despite spending years in the states, he never develops the American habit of tell all, so a certain amount of reading between the lines is necessary; however, what he doesn't spell out about his relationship with each of his three wives, his daughters fill in.

The period of letters from 1951 to 1957 finds Alan Watts at the American Academy of Asian Studies in California. Here his thoughts return fully to his first passion for Eastern philosophy and spirituality. If your primary reason for reading is to know more of his thoughts on Vedanta, Buddhism, Hinduism, the Tao and Zen, then skip straight to this section. Besides his philosophical musings, we see the difficulty of setting up an institution, getting funding, deciding on its mission and organizational power struggles. This is a prolific period in which he writes some of his best known books, lectures around the country and internationally and finally travels several times to Kyoto, Japan. Socially, he is popular and has longstanding friendships and letters with Aldous Huxley, Henry Miller, Timothy Leary, Joseph Campbell, and many other notable people.

In the late 1950's, Alan Watts becomes involved in the psychedelic experiments with LSD-25. In one letter, he advises a fan that if one doesn't learn what one needs to learn within 10 trips on LSD, then one never will. For him, the drug was a tool for consciousness raising, not a lifestyle. In the last years of his life, he sends out quite a few letters hoping to deter lawmakers from criminalizing LSD and expounding on his view that police should stay out of our moral lives and not be what he calls armed clergy. His foresight into what would eventually become the drug war shows him to be alarmingly prescient.

In the early 60's, he is again divorced and later marries his third wife, Jano. The love letters in this section are his most intimate writing. Previous to this we see how he writes to his family, his publisher and, his fans within socially acceptable limits. Even to his own parents, he restricts his description of his broken home, asking that they accept that it is so. He's been criticized for repeatedly straying from his marital partners, but I never got the sense that he saw himself as a Lothario. If anything, he is amazed that women began to find him more attractive as he aged. His daughter confirms him as a man with remarkably bad sense in choosing all of his wives.

His workaholic lifestyle and alcoholism eventually take a toll on his energy, performance, and viewpoints. His last letters, while erudite, can feel like the the unrelenting editorial of an armchair alcoholic. Even so, some of the most captivating letters were also written at this point in time. His views on politics still seem relevant in 2018.

“I am not one of those who believes that it is any necessary virtue in the philosopher to spend his life defending a consistent position.” From a young, clueless Englishman ignorant of American social classes and race at the beginning of his life in America to writing letters to Congress to protect worship in the Native American Church in his last years, what is perhaps most compelling is seeing how an intellectually rigorous scholar can flow with the times, live, love and learn.

Recommended, especially for fans of Alan Watts and scholars of comparative religions

~review by Larissa Carlson

Edited by: Joan Watts & Anne Watts

New World Library, 2017

pp. 599, $32.50