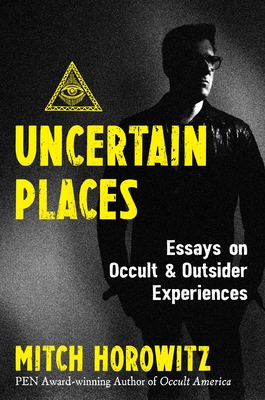

Mitch Horowitz is a well-known writer and speaker about what he enthusiastically calls “New Age” themes. He’s a wealth of information, and as a scholar-participant, he’s independent, not tied to any academic institution. For a long time, he was a vice-president at Penguin Random House and editor-in-chief of a division for metaphysical books.

There’s some interesting material in this collection of essays. One of Horowitz’s major points is that “metaphysics and modernist thought have never fully gotten along.” In his introduction, Horowitz defines the occult as “a freeform spiritual philosophy that draws upon or remakes ancient traditions but exists outside of any single doctrine, liturgy, or congregation.” Its “philosophical gambit is that there exist unseen dimensions whose forces can be felt on and through us.” Horowitz writes that “generativity” is “the essential human need.” The spiritual search, he believes, “is the search for power,” meaning “humanity’s wish to construct, strive, make and grow.”

The collection includes an overview piece about the import of southern California occultist Manley P. Hall in which Horowitz speculates on how Ronald Reagan’s speeches and his whole “City on a Hill” inspirational message drew on themes he got from Hall. In another of the essays, written upon the death of James Randi, the professional “skeptic” who outed fraudulent psychics, Horowitz argues that Randi’s real legacy was not so much to expose con artists, but to deter legitimate interest in and research about ESP.

There’s an essay called “The War on Witches,” in which Horowitz documents the recent worldwide increase in violence aimed at people (mostly women) accused of being “witches.” It’s happening in Africa, the Pacific, Latin America, and in immigrant communities in the U.S. This rise in actual witch-hunting (as opposed to the political, rhetorical use of the term “witch hunt”) is an important phenomenon, not just for the victims but for what it says about the many places where this violence is on the rise. Horowitz is a good journalist here, but he lacks analysis and explanation.

Here’s an example of some muddled thinking. He writes that it’s tempting to link increased rates of violence toward “witches” to poverty and scapegoating—as if these aren’t perennial social facts--but that there are “contemporary triggers” such as young, alienated men seeking status by targeting witches; the prevalence of Pentecostal churches; and the singling out of poor women and widows, for the purpose of seizing their property. This is facile. Pentecostal churches have been prominent in poor countries for decades, and there’s nothing recent about alienated young people seeking status, let alone women being charged with witchcraft by someone who wants to steal what they own. We’re left with an unexplained phenomenon, which may as yet be just too complex to explain.

In an essay called “God of the Outsiders,” and in other writings and talks apart from this book, Horowitz advocates that “Satanism” is a legitimate spiritual, ethical, and intellectual path. By “Satanism,” he’s not talking about a metaphor for one ‘s psychological shadow. He believes in Satan as a god, and he says that there’s an “esoteric history behind the Satanic which the mainstream culture has failed to appreciate.” That’s because of a misreading of Genesis Chapter 3. The serpent was really Eve’s liberator, and if knowledge of good and evil had not been introduced into the world by the adversarial force represented by the serpent, “everything and everyone would have been classified by a certain sameness.” Instead, Satan is a kind of “philosophical grandfather” for the Romantic poets and more generally, for “artists, rebels and political agitators.”

Okay, this is interesting. My understanding is that some or many of the Romantic poets did view Satan as a figure of rebellion, and there is art in that. And, anyone who’s an occultist has and should enjoy the freedom to worship any god they’d like. To each their own. That’s not what gives me pause.

Horowitz is, apparently, an acolyte of a man whom he calls “brilliant,” Michael A. Aquino, who died in 2019. Colonel Aquino split off from the Church of Stan and founded his own Temple of Set in 1975. Apart from his religious practice, Aquino has a sordid reputation, which I won’t go into here; it’s available in the public record. I really don’t care what Aquino, Horowitz or the small number of people who call themselves Setians believe about “self-deification” and an Egyptian-derived being called Set.

My quibble with Horowitz’s book, published in 2022, is that he does not tell readers--even in a footnote—fully who Michael A. Aquino was, instead identifying him only as “a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army.” Aquino was an expert on constructing psychological warfare operations aimed at civilian, domestic populations. Among other things, he co-authored a short treatise, “From PSYOP to Mind Wars: The Psychology of Victory” with Colonel Paul E. Vallely. (It’s on-line.) Colonel Vallely is still alive and active. He’s a Qanon conspiracy theorist who has boasted about being part of Donald Trump’s shadow clique of military “intelligence officers.” There’s more to these unsavory backgrounds, but it’s not my job in a book review to detail it.

Horowitz promotes himself as an iconoclast and a renegade. That has left me scratching my head as to why he adulates Michael A. Aquino without cluing his readers in. Especially in our current era of disinformation-fueled violence and chicanery, it is incumbent upon journalists to tell us who their heroes are, and why.

In general, I found this book to be underwhelming, and on this one score, I found it to be disturbing.

~review by: Sara R. Diamond

Author: Mitch Horowitz

Inner Traditions, 2022

294 pp., $19.99