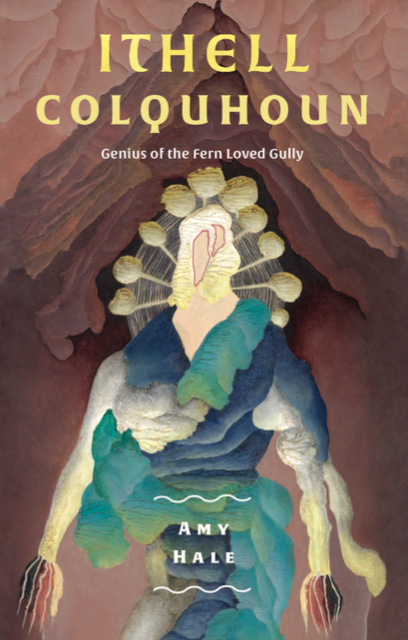

Amy Hale (PhD, Folklore and Mythology, UCLA) is a well-established scholar, researcher, and teacher. In addition to being the author of Genius of the Fern Loved Gully, she edited Essays on Women in Esotericism: Beyond Seeresses and Sea Priestesses (Palgrave 2021), and wrote introductions for the extraordinary Decad of Intelligence (Fulgur 2017) and Ithell Colquhoun: Taro as Colour (Fulgur 2018) (reviewed in Mythlore 40.1 Fall/Winter 2021). The Taro as Colour introduction focuses on what many regard as Ithell Colquhoun’s (1906–1988) greatest accomplishment: her Tarot deck and the various influences, particularly that of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, that inform it. Genius of the Fern Loved Gully is a biography of the artist including in-depth examinations of the wide range of artistic, metaphysical, and other subjects that Colquhoun explored; the esoteric and occult groups that she joined and participated in; and a number of color illustrations of her art and visual images articulating some of her metaphysical ideas. It also includes notes, an index, biography, photographs, and color illustrations, and provides valuable information about the influence of the Golden Dawn during the mid-twentieth century. That influence flowed in significant part from the publication of the Rider-Waite Tarot (1909) by members Arthur E. Waite (1857–1942) and artist Pamela Colman Smith (1878–1951) and post-dates the days of Waite’s Golden Dawn group the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross. Where Waite and Smith were part of the generation that actually participated in the events that have become part of the Order’s early history, Colquhoun, who was born in 1906, had to search for individuals who had been directly involved with it who might also provide her with instruction about its teachings.

Colquhoun was a prolific artist who apparently saved every doodle and note she put to paper. She was also an energetic communicator who enjoyed many acquaintances, friendships, and involvements with esoteric and occult groups. Sorting the resulting wealth of documents and art and aligning it with her intellectual pursuits and connections demanded a great deal of time and attention and Hale clearly gave Colquhoun her all. She opted for a combined chronological and thematic organization of her research material and created a diagram—an inverted triangle within a triangle—to help the reader through the cornucopia of art, life experiences, and multiple interests and enthusiasms. The top left of the larger triangle is labelled Surrealism, the top right is labelled Occultism, and at the bottom of the overlayed larger and smaller triangles is Celticism. A horizontal line creates the smaller triangle marked “Finding Colquhoun” on one side and “The Legacy” on the other. These labels match chapters in the book.

Chapter I “Finding Colquhoun” outlines Hale’s discovery of the artist and her work in relation to her life in Cornwall, first examining the then (2000) uncatalogued collection at the Tate and later at the National Trust estate, Lanhydrock, near Bodmin, where her Tarot cards of 1977 were located. Here, readers also learn about Colquhoun’s birth in India (1906), early childhood, and her later education, as they paralleled events in the larger world: the World Wars, the Russian Revolution, changing social hierarchies, and the development of occultism. While all of these are important to understanding Colquhoun’s oeuvre, this last and her commitment to personal development and enlightenment are vital.

Chapter II “Already I knew my own mind” points to some of the specific ways that Colquhoun’s experiences growing up and her family context, notably the association by birth with India and also her Scottish and Irish ancestral lineage, affected her notions of personal identity and led her, at the age of ten, to the realization that she wanted to paint. In the 1920s, she received an excellent general education followed by several years at the Slade, from which she graduated in 1930. She then travelled a great deal before settling in London, where she began exhibiting and accepted commissions of interest to her.

Chapter III “Surrealism” emphasizes the importance of surrealism to her, particularly after the 1936 Surrealist Exhibition, and also the role esotericism had on her development as a surrealist and eventual distancing from the group. A number of her paintings of the late 1930s demonstrate the combination of surrealist ideas, such as convulsive beauty, with Arthurian myths about the sacred land, the waste land, and the king or god that must die to rejuvenate it. She also furthered her interest in magic, including sex magic, in connection with the evolution of the individual and society at large. Her marriage to the surrealist Toni del Renzio also lasted through this period (until 1947) and inspired an interest in politics and social revolution, but most important to her future Tarot deck was Roberto Matta’s concept of psychological morphology, which directed surrealist automatism away from Freudianism and allowed it to embrace larger ideas about the fourth dimension. After her divorce, she set up a studio in Lamorna, Vow Cave, Cornwall, dividing her time between it and her London home, and also continued to direct her magical practice toward the goal of personal enlightenment. Specifically, she worked with the idea that automatism and dreams do not merely offer an avenue of communication with one’s unconscious, they also access realms occupied by non-human entities. Connection and communication with these beings was, she believed, fostered by the use of esoteric symbolic systems.

Chapter IV “Celticism” addresses the close bond Colquhoun felt with all things Celtic thanks to her ancestry, a bond that accounts for her romanticized interest in Cornwall, its landscapes and history. She, like many, believed there was such a thing as Celtic spirituality and even became a practicing Druid. Celtic spirituality, like many of the occult and esoteric groups of the day, was committed to the idea that there had once been a more spiritual, more “traditional” society that was now known only to those who had been initiated. Colquhoun’s introduction to many of these ideas came about in part through her fascination with W.B. Yeats, whose work she studied closely and over a long period of time, and Robert Graves’s The White Goddess. It is hardly a surprise that the artist who created “Dance of the Nine Opals” (1942) also became involved with ritual celebrations of the equinoxes.

Chapter V “Occultism” addresses Colquhoun’s interest in magic and correspondences, including those aligning kabbalah, Tarot, numbers, planets, and so forth, as the central and most continuous commitment of her entire career. As Hale points out, her early life receives a lot more attention from historians insofar as occultism is concerned than does her later life. She points out that this weighted interest is misleading for anyone seeking to understand the mid-twentieth century and Colquhoun’s work. This is the period when Crowley’s work and the O.T.O. became more widely known, and also when notions about the fourth dimension, Atlantis, Wicca, witchcraft, and Druidry found some popularity or perhaps notoriety. Throughout her mid- to later life, Colquhoun refined her understanding of esotericism in relation to color theory, the Golden Dawn, and other themes through initiation into an astonishing array of groups: “the O.T.O., Co-Masonry, Martinism, British Circle of the Universal Bond (also known as ADUB), the Golden Section Society, and in later years the Fellowship of Isis” (167).

In this chapter, Hale reviews Colquhoun’s lifelong interest in the occult, particularly alchemy and development of related themes in her art, such as the divine androgyne, and her studies of witchcraft and attempts to find and join a group with Golden Dawn affiliations. Sections are devoted to colour and forms, such as the tesseract, and tracing the artist’s experiments in these areas to art works demonstrating the sophistication of her grasp of them. Among these works are her “Taro” deck (1977) and “The Decad of Intelligence” (1978-79), ten enamel depictions of the sephiroth of the kabbalah (Fulgur 2017).

Chapter VI “The Legacy” is a brief description of the artist’s later years, her isolation, poor health, the somewhat confusing terms of her will, and the inspiration that her life and work lent to other artists. Comparisons with Pamela Colman Smith’s legacy and final years, which were also spent in Cornwall, will come readily to the minds of readers familiar with that artist’s history.

Should, or rather when, Genius of the Fern Loved Gully goes to a second edition, the only improvements that might be made are the addition of more illustrations (there can never be too many illustrations) and a chronology. The interwoven development of Colquhoun’s numerous interests is challenging to follow and a few pages listing high points in her career, important meetings, group affiliations, and so forth, would be a tremendous aid to the reader. Genius of the Fern Loved Gully is a must have for anyone wanting to know more about Ithell Colqhoun and her art and Taro deck (Fulgur Press 2021), as well as the contexts and sources available to mid-twentieth-century seekers.

—review by Emily E. Auger

Author: Amy Hale

Strange Attractor Press, 2020

pp. 304 pp. Paperback $24.95