This is a beautiful book, an ode to the forest, a memoir of sorts, an almanac. The Healing Tree is a revised and updated version of Priestess Stephanie Rose Bird’s 2008 book A Healing Grove. This new volume begins with a prologue written in 2023 and the preface she wrote in 2008. Bird calls what she’s doing a “reclaiming” of the deeply rooted traditions of African and African-American nature medicine.

Bird begins the 2023 prologue by invoking the word shinrin-yoku, the Japanese term for forest bathing, a healing mainstay. She observes that for indigenous Africans, trees are life. But then juxtaposes this fact -- and the wisdom of forest bathing -- with another reality: for Black and Brown people, especially in the United States, trees and forests have not been reliable havens—to say the least. Recall the recent 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery, chased and killed by white men in “a tree-rich place in Georgia.” He wasn’t “supposed” to be there. Present-day lynching is a reality in the long history of white terrorism against Black people. Perverse, also, is the verbal connotation that the word “urban” has become media speak for “where Black people live.” This is why African and African-American reclaiming of the forest is imperative.

Bird is a perfect storyteller, steeped as she is in the knowledge and wisdom of plants, ancestry, and magick, and the rootedness of having lived her own life in different kinds of places. She tells how she grew up in a rural area at “the end of a dirt road.” At a time when most African American families had migrated from the rural South to cities, her parents did the reverse, while not all of her relatives resonated with the woods. Bird now lives in Illinois, among the oaks. She writes that one of her recurring themes “is the acknowledgment of urban herbalists…. Wherever you live, you can still be an African-inspired herbalist.” Historically, she writes, trees have been markers for African Americans, starting with the planting of evergreen trees at burial sites. All kinds of pine trees have been used medicinally and Bird gives us her personal recipe for a pine floor wash, a tonic for grief, depression, and fatigue.

In between tree lore, Bird weaves the story of her ancestry. “As African Americans,” she writes, “we were a disenfranchised group. For many years, we felt we would never know where our true homes were.” Bird often speaks and writes about West Africa because of its “well-defined modalities that crystallize the meaning of African holistic health” and because much African American spirituality “stems from West Africa’s coastal people.” Bird found through her own DNA testing “and the study of deep ancestry” that she is not of West African ancestry at all, but instead, she’s part of the Bantu speakers migration that led her ancestors south from East Africa. Plus, she has a secondary Mediterranean ancestry—Balkan, Portuguese, Spanish, and Moroccan.

Everywhere, there are tree cultures. Enslaved Africans in the United States were forced to convert to some form of Christianity. Yet, Bird writes, “It was to the forest that early African Americans stole away to form congregations, to sing and pray.” Some became masters of a practice called Jiridon, tree whisperers, observers of nature, communicating a language of trees.

Part almanac, this book is a feast, full of remedies and recipes. I flipped, randomly (and appreciatively) to a graphic on the nutritional benefits of chocolate! And then to Bird’s recipe for an acai smoothie. Nuts, oils, leaves, needles, barks, palms, pods, resins—all the medicines of trees are in this book, well-indexed, with a good glossary, footnotes, and an appendix about how to contact Bird about her six-month Earthwise apprenticeship.

The book’s Epilogue, “Seeds of Hope,” emphasizes the commitment of African and African-descended people to environmental sustainability and ecological lifestyle choices. Bird highlights the work of the Green Belt Movement (GBM), founded by Wangari Maathai of Kenya. The GBM focuses regionally on stemming threats of deforestation, preserving water and sustainable farming methods, and specifically on occupational training for African women. Bird ends with something every reader can do: buy chocolate and other products that are both organic and that meet the economic and ecological standards of FLO, the Fairtrade Labelling Organization International. This is one way, she concludes, to “build community and ecology, step by step.”

~review by Sara R. Diamond

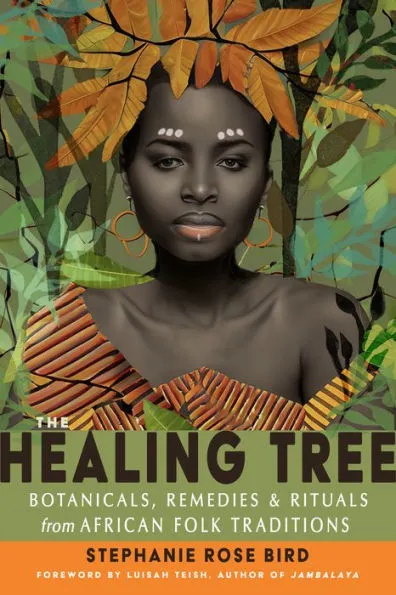

Author: Stephanie Rose Bird

Weiser Books, 2024

298 pages, $26.95